During the planning phase of the Vlad Tepes World Tour I had been congratulating myself for not being in Turkey during Ramadan, something I knew would lead to complications in terms of services, particularly in more remote areas such as where we were headed next.

I, uh, apparently didn’t do my homework well enough.

We did actually arrive in Turkey after Ramadan was over. We neglected, however, to check for other holidays. Such as Kurban Bayramı, a festival I now fondly refer to as “The Festival of Lamb Intestines”.

The first inkling we had that something was not entirely right was the sight of animal intestines lying in the gutter in the Fatih neighborhood of Istanbul towards the very end of our stay in the city before heading into Western Anatolia to the town of Emet. At first, we just thought maybe we were near a butcher shop or a serial killer had been mistakenly set free.

Then we saw more intestines. Damn, that’s one dedicated serial killer.

By this time we were due on the (very) long bus to Emet, so without thinking too much of it we got on board the bus for a nice little ten hour or so bus trip down through Turkey’s interior where my seatmate, despite very little English and with little patience for my translation program insisted on taking us for tea at one of the stops and otherwise being a fascinating conversationalist, by which I mean we used a lot of hand signals and exchange of passports.

Ceramics from the province. Much of the ceramic tile work in Istanbul’s mosques is from this region.

(He was returning home from Saudi Arabia, a point made by enthusiastically showing me his passport stamp – I didn’t realize it at the time, but my guess is he was returning from the Hajj, a supposition supported by his generous use of prayer beads during the trip as he struggled to avoid murdering the small child seated behind us who spent most of the trip testing my seatmate’s patience).

Towards the end of the trip – Emet was the second to last stop, so most of the passengers had already disembarked as we entered the hills engulfing Emet and its boron mine (apparently, the source for a fairly impressive percentage of the world’s boron) – the bus attendant and bus driver on one side, and my traveling companions and I on the other spent a fascinating effort in technology and language difficulties as we passed my iPad with its Turkish translation program on it.

By fascinating effort, of course I mean hysterically funny and utterly hopeless effort. As it turns out, Turkish and English are grammatically very, very different. Specifically, Turkish is agglutinative, much like German or Classical Nahuatl (Aztec, which I studied in college). Where the translation programs extant today actually do a pretty credible job of translating things like Romanian to English, Turkish to English, well, let’s just say not so much.

We spent the better part of the last two hours of the trip trading the iPad back and forth between the two groups, scratching our heads and trying to translate the most bizarre sentences I have seen this side of an H.P. Lovecraft dream sequence.

Finally, as night quickly advanced over the hills, we arrived in Emet, our staging ground for a trip to some nearby Roman ruins (these had nothing to do with Vlad Țepeș but were well-preserved, close, and the location of the world’s first stock market) and, much more importantly to me, the ruins of Eğrigöz. More about that last later.

Emet isn’t exactly a hopping, cosmopolitan part of Turkey. It is known for exactly two things; a sprawling thermal spa resort, and a boron mine. Given the general lack of hotels in an area like this, we had booked a room in the thermal spa resort (though only one of us wound up taking advantage of the facilities – I was there for adventure, and I was deeply concerned that being too comfortable might negatively impact that).

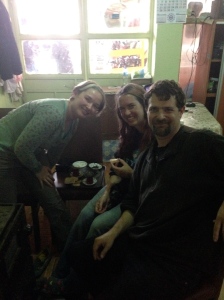

Hiking through Emet after dark was an interesting experience of its own, and by the time we arrived at the resort we soon realized that rumors of some resort personnel speaking English was, perhaps, a little optimistic of an interpretation. To be sure, getting checked in was no problem, but how were they going to explain to three American travelers that the four-day long Lamb Intestine Festival meant that car rentals were closed, getting a driver was next to impossible, and if we wanted to see the ruins that I had just traveled thousands of miles across the world to see with only days left in Turkey, we might have to walk.

Hiking through Emet after dark was an interesting experience of its own, and by the time we arrived at the resort we soon realized that rumors of some resort personnel speaking English was, perhaps, a little optimistic of an interpretation. To be sure, getting checked in was no problem, but how were they going to explain to three American travelers that the four-day long Lamb Intestine Festival meant that car rentals were closed, getting a driver was next to impossible, and if we wanted to see the ruins that I had just traveled thousands of miles across the world to see with only days left in Turkey, we might have to walk.

After an hour or so of sweating bullets I bit the bullet and called the friend from Turkey who had helped us earlier with both bus tickets and resort reservations (the Internet fails when you are navigating in a world of gender segregated buses and rampant online fraud, apparently) and put her on the phone with the man at the front desk.

Finally, the next morning we had it settled: a friend of the manager was willing to loan us a car. Well, and, as it turned out, a driver (whose name we never got and whom we later discovered was a taxi driver who decided earning a couple of hundred lira to drive some Americans around wasn’t a bad few hours work).

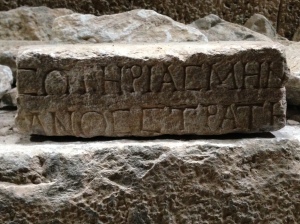

Which is how we made our way to Çavdarhisar, a small town that is distinguished in that it sits in the middle of the ruins of Aizanoi, most lately a Roman ruin, but in earlier times also a Byzantine and, even earlier, a Greek city.

Aizanoi’s ruins are in remarkably good shape, and consist primarily of a mostly-intact Temple of Zeus, a stock market, public baths, the theater-stadium, a necropolis and a sanctuary to the Anatolian Earth Mother goddess Meter Steunene, which unfortunately is largely buried and undergoing excavation, so wasn’t visible for viewing.On the way back, our new friend and driver stopped at one of the ever-present roadside fountains and saw…this. Yes, more lamb intestines. With no common language it wasn’t until later with the help of a teacher we befriended at the resort that we learned the gist of it:

From Wikipedia:

Eid al-Adha (Arabic: عيد الأضحى ʿīd al-aḍḥā, “festival of the sacrifice”), also called Feast of the Sacrifice, the Major Festival, the Greater Eid, Kurban Bayram (Turkish: Kurban Bayramı; Bosnian: kurban-bajram), or Eid e Qurban (Persian: عید قربان), is the second of two religious holidays celebrated by Muslims worldwide each year.

It honours the willingness of Abraham (Ibrahim) to sacrifice his young first-born son Ishmael (Ismail])a as an act of submission to God’s command and his son’s acceptance to being sacrificed, before God intervened to provide Abraham with a lamb to sacrifice instead.

Ah-ha. That explains the lamb intestines everywhere.

Ah-ha. That explains the lamb intestines everywhere.

Another interesting fact about this feast is that – as our Turkish friend explained to us in passable English – in Islam animals have no souls, but those animals who are sacrificed during the Feast of the Sacrifice are allowed into Heaven.

I didn’t ask the sheep we passed for their feelings on the matter; it seemed likely to be a touchy subject.

The final non-traveling day of our trip – not just in Turkey, but for the entire trip – we visited what was one of the three places I had determined to see on the trip, and the entirety of the reason for going to Turkey on this trip – the ruins of the Ottoman fortress of Eğrigöz (pronounced – as I unfortunately was to figure out only once I returned to the United States, “eh-ree-gooz” – though that explains the strange expressions I got from locals).

Surveyor’s map of the fortress. The village is on the left (west), the river on the right (east). With the exception of the western approach, sheer cliff face would discourage any thought of escape or assault.

Eğrigöz (the fortress) sits adjacent a modern day village (also called Eğrigöz), perched up against the river on an incredibly steep outcropping. It is not, it should be noted, large – the entire walled area was only a couple of hundred feet probably, and as I later put together afterwards, the actual “citadel” part of it was a keep only modestly larger than Poenari Castle in Romania, Vlad Țepeș‘s prized fortress perched high in the Carpathian Mountains which we had visited the previous week.

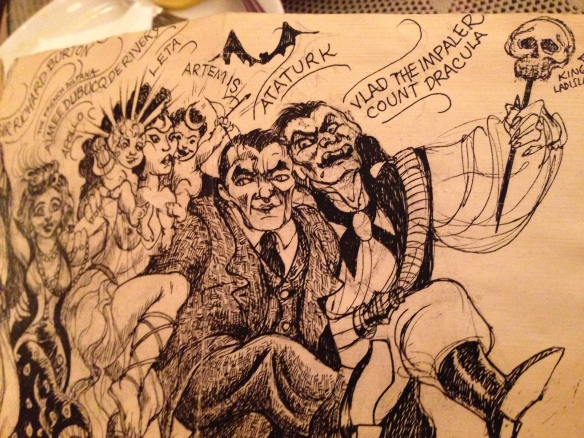

Symbol of the Order of the Dragon, an anti-Ottoman, pro-Roman Catholic military order that Vlad’s father belonged to – it is the origin of the name “Dracula”, meaning “Son of the Dragon”.

On arrival to Eğrigöz the value of the location was instantly obvious. Yes, it dominated the river valley it sat over, but it was also a brutally long way from Europe and any possible hope of rescue or escape. By comparison, Edirne would have been a cakewalk.

Vlad Țepeș and his brother were hostages, but they were noble hostages, and as such they were trained in academic and martial subjects with contact – it’s unclear whether at Eğrigöz, Edirne, or some other location – with the sultan’s son, Mehmed II (who would later, it should be noted, be the man who finally conquered Constantinople and moved the capital of the Ottoman Empire to Istanbul).

There is precious little beyond this that we know of those years. We know Vlad was not fond of Mehmed, though it never got so bad as to interfere with Vlad in later years working out certain political “arrangements” with Mehmed’s father, Murad.

There are, as well, stories that Mehmed and Radu the Handsome – Vlad’s younger brother – got along, um, very, very well. (Naturally, these stories are vehemently denied by Turkish historians, but given Radu’s relative obscurity and the reverence with which Mehmed II would later be held in, it seems quite plausible).

Years later, Vlad would be freed, making political arrangements with the sultan and taking his hard-won knowledge of military tactics and Turkish to great effect when his boyhood companion, Mehmed II, marched into Wallachia and tried to burn down Vlad’s realm.

Gatehouse of Eğrigöz Fortess from below. The well-preserved gatehouse is all that remains of the central keep.

So there at the end of the Vlad Tepes World Tour, we hit not the very beginning, perhaps, but very close to Vlad’s beginning.

Perhaps, too, one can argue that Eğrigöz was a psychological birth of sorts for Vlad, as it was there that he learned about the enemies – Ottomans and his brother Radu alike – that would hound him for the remainder of his life. There, too, he learned the skills that would keep him alive through three reigns until his death led to his body staying in Wallachia, but his head making one final trip to Istanbul to give testament of his death to Mehmed II.

So after four days in Emet, my traveling companions and I made our way back to Istanbul, and from there onto a plane back home.

At least until next time. After all, we never did make it to Moldova or Giurgiu…